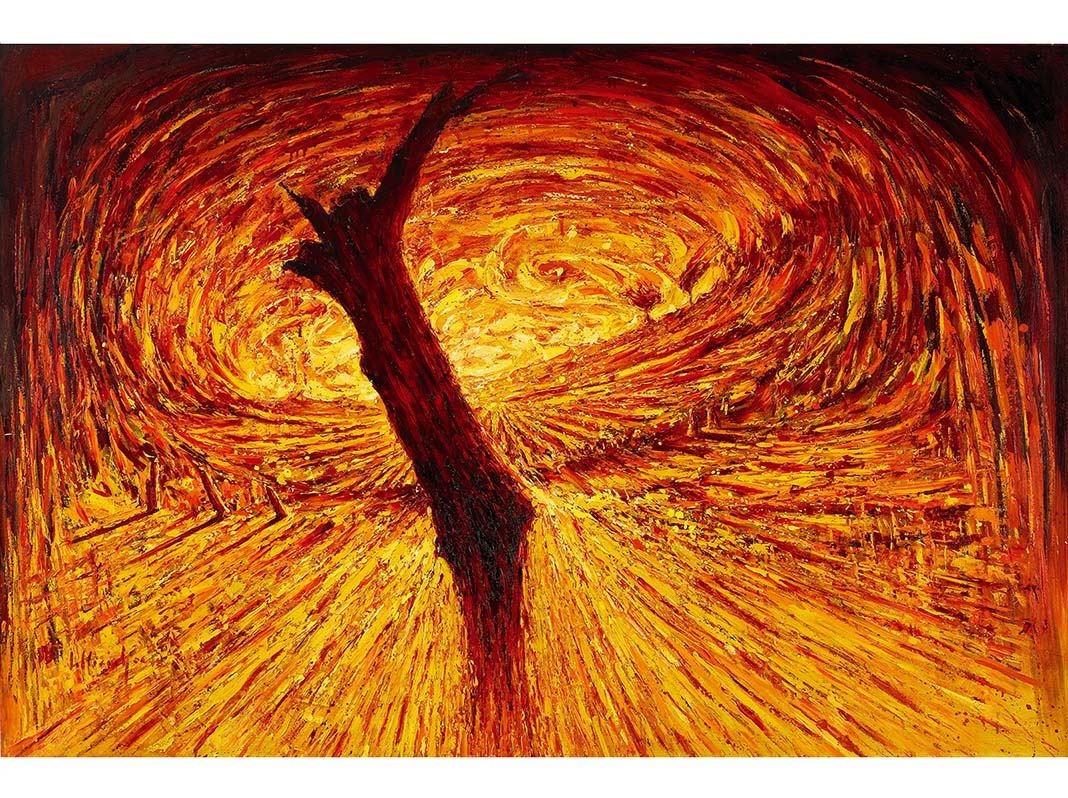

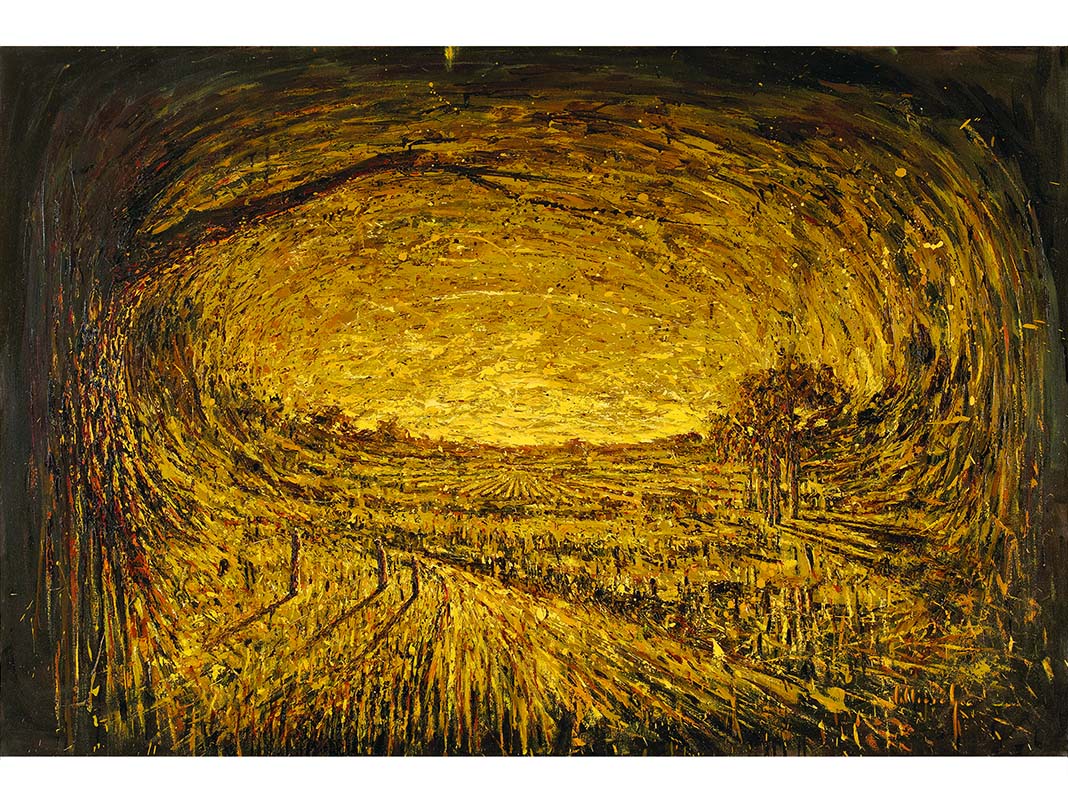

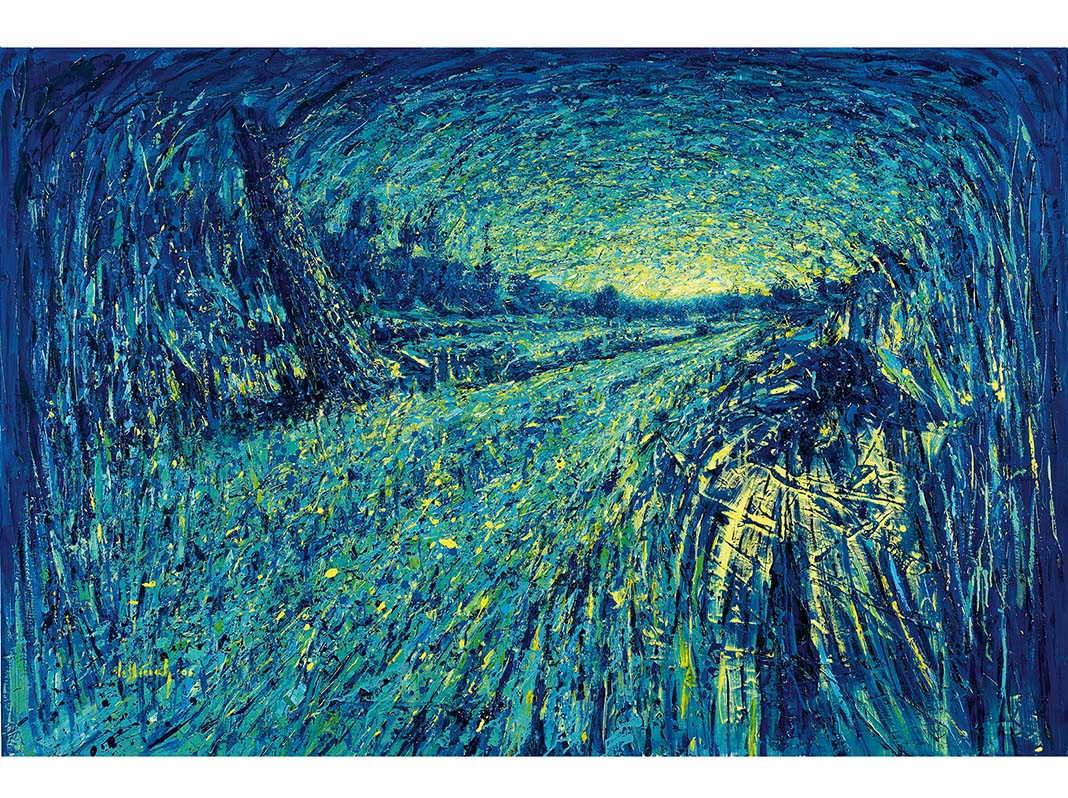

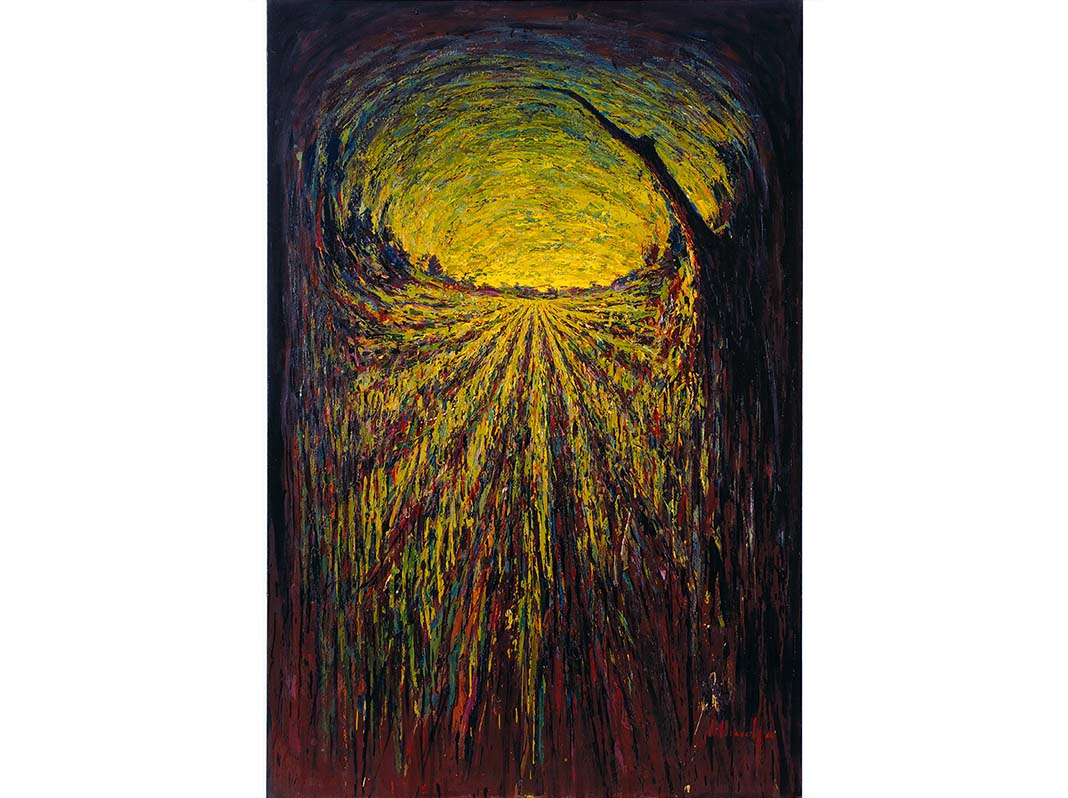

The mood of the paintings is at times broodingly Gothic, at times more Romantic, and here one can sense the moods of the forest at Selvino and a life lived mainly in a European environment. The application of the paint, however, takes the viewer on another journey.r>

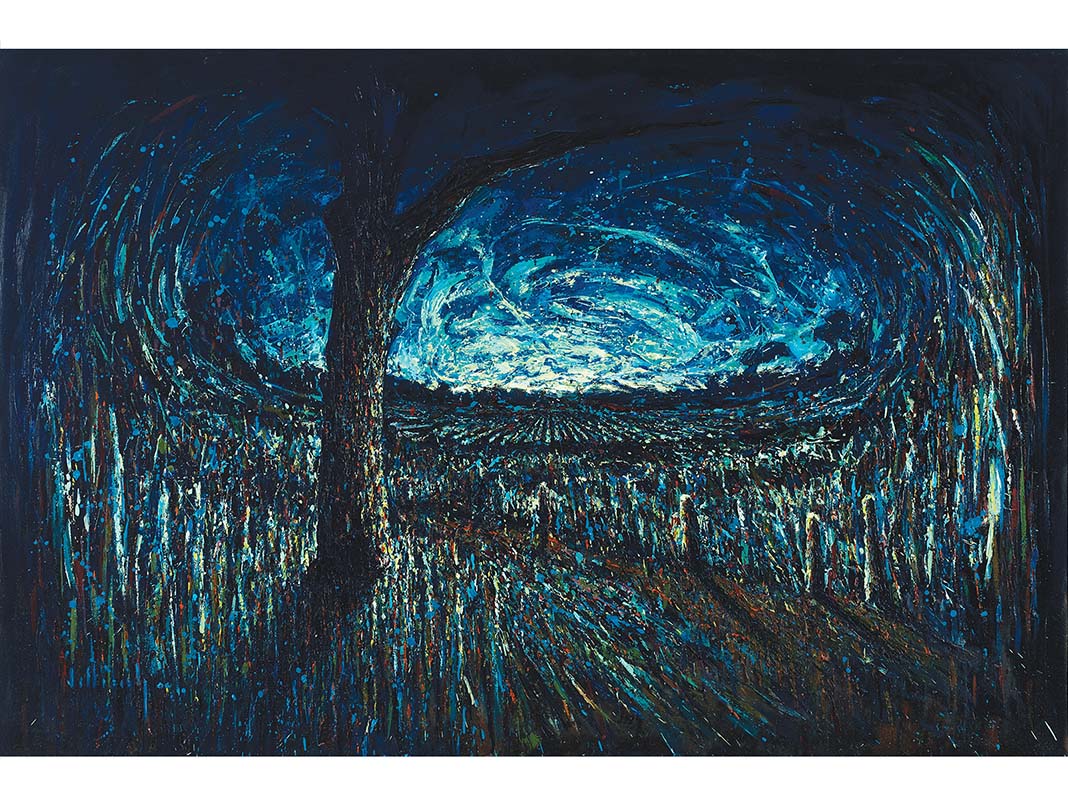

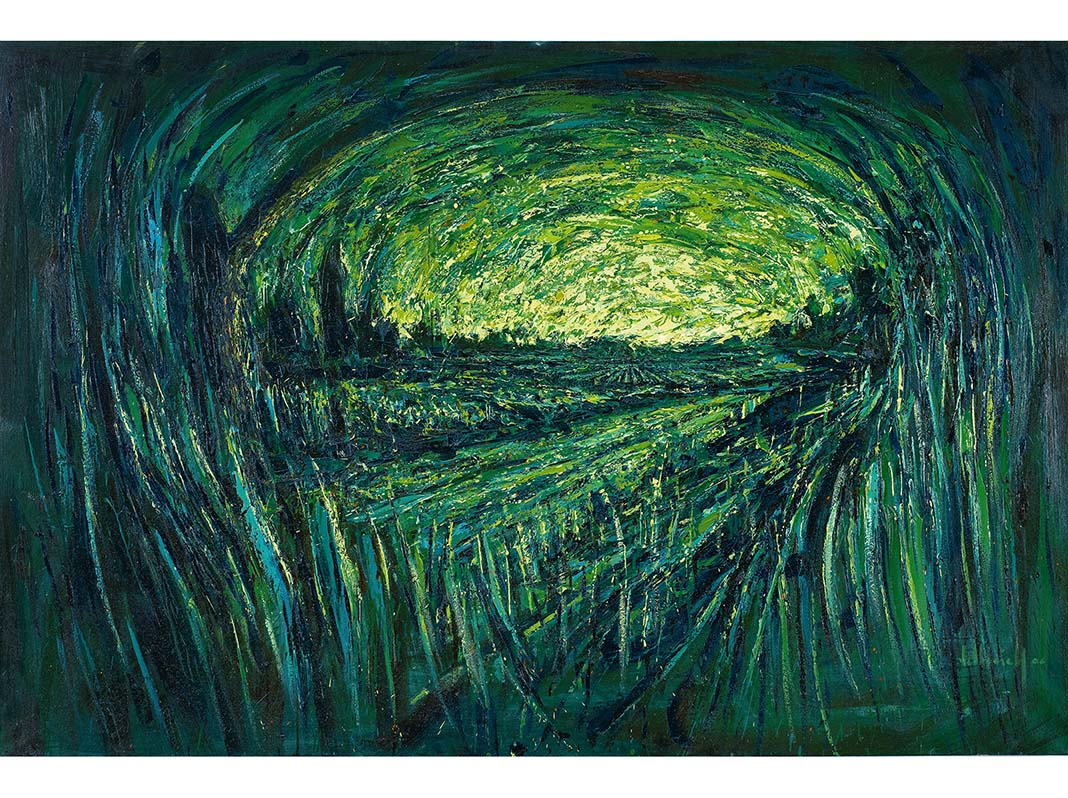

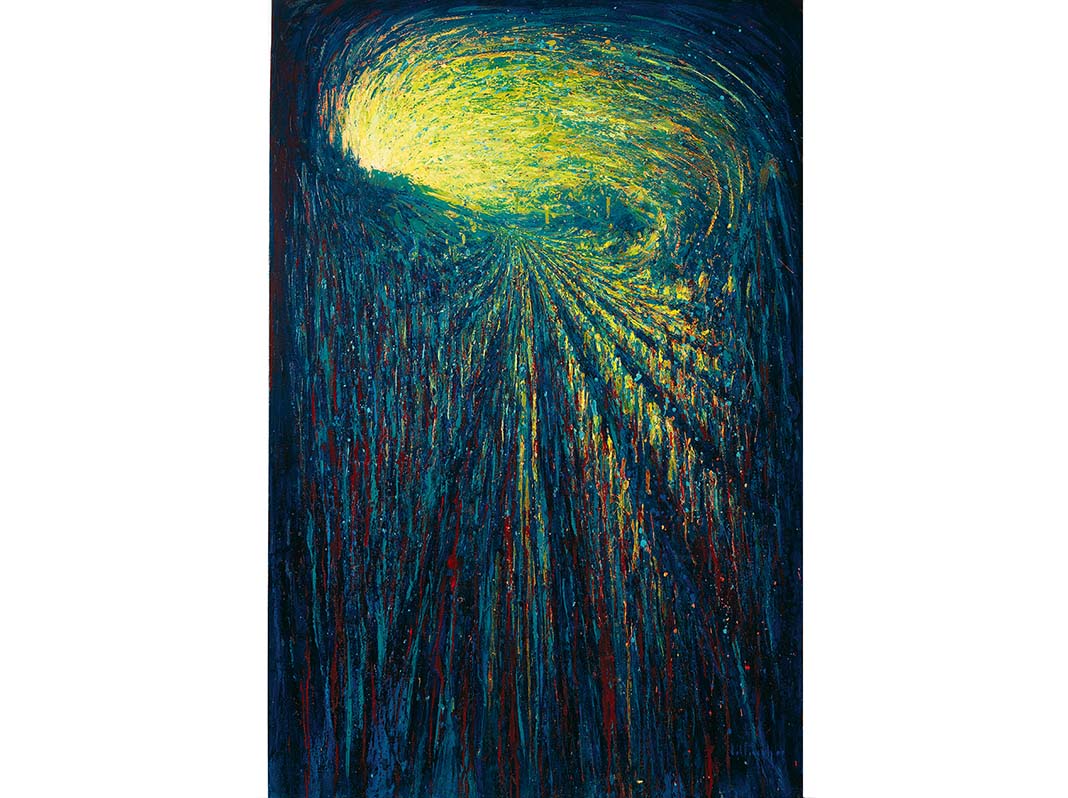

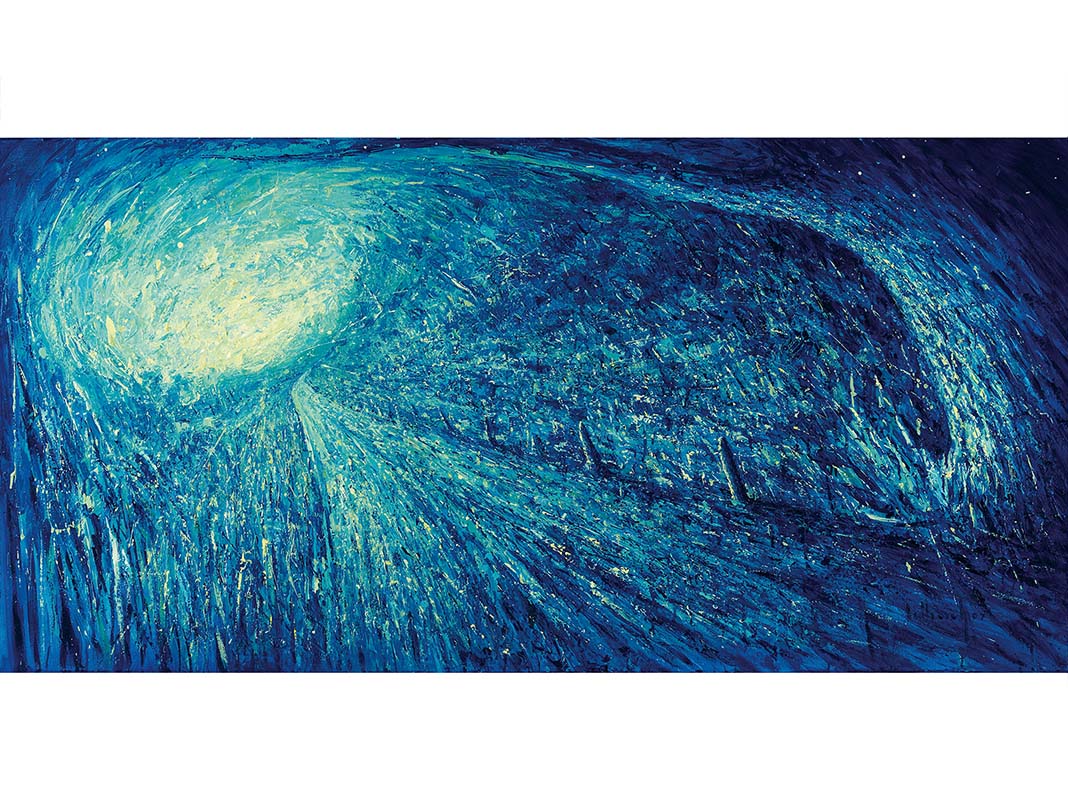

The visual language Villicich has developed to convey his view of nature is to stress the surface of the canvas before applying any colour. Working quickly and instinctively, he splatters the primed canvas with multi-directional splotches, lines and curves of pure gesso. This is both a conscious and intuitive process, reminiscent of the way Jackson Pollock viewed his technique of applying paint, not as random, but as ‘controlled chaos’. As nature is never entirely rhythmical or repetitive, Villicich has mastered a way of applying the gesso to render this sense of an unending and unpredictable flow of energy. The surface is alive with tension and movement. A flat surface, to Villicich, signifies death.

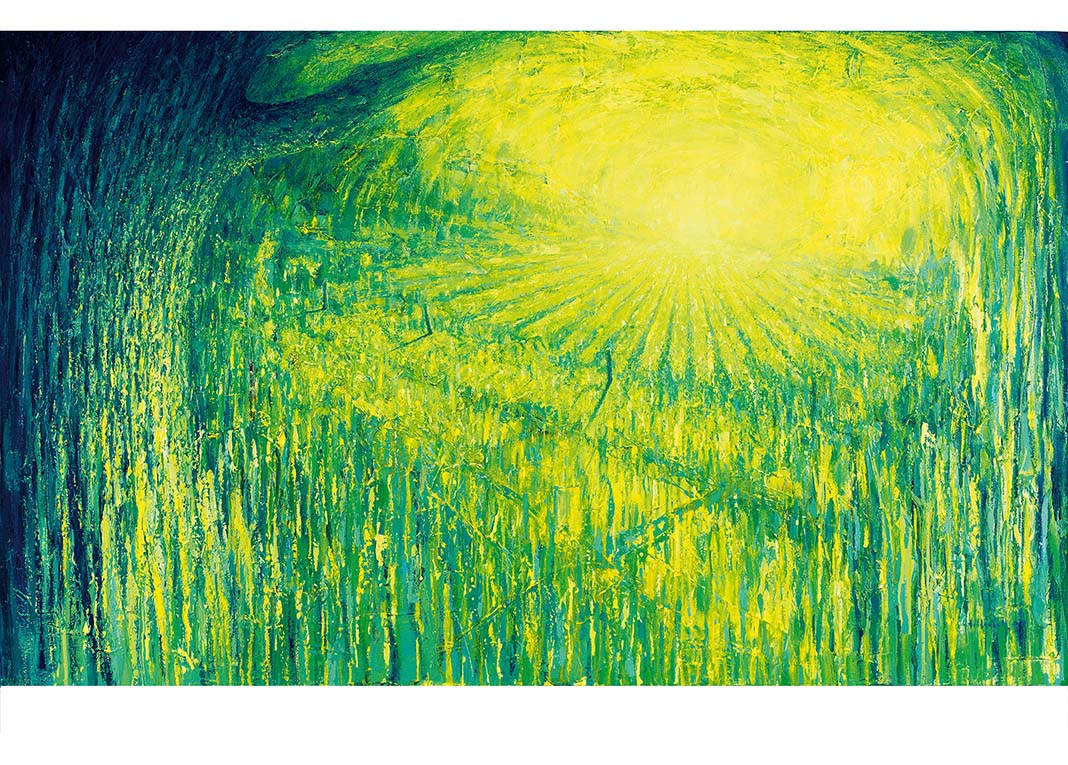

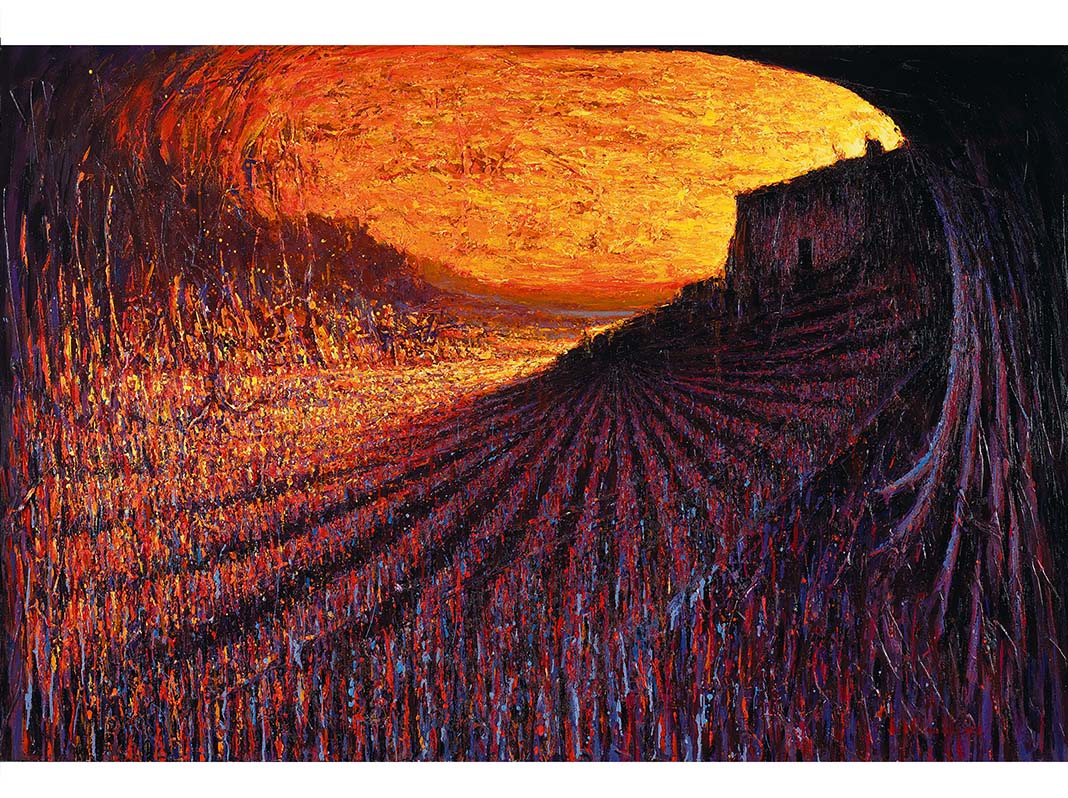

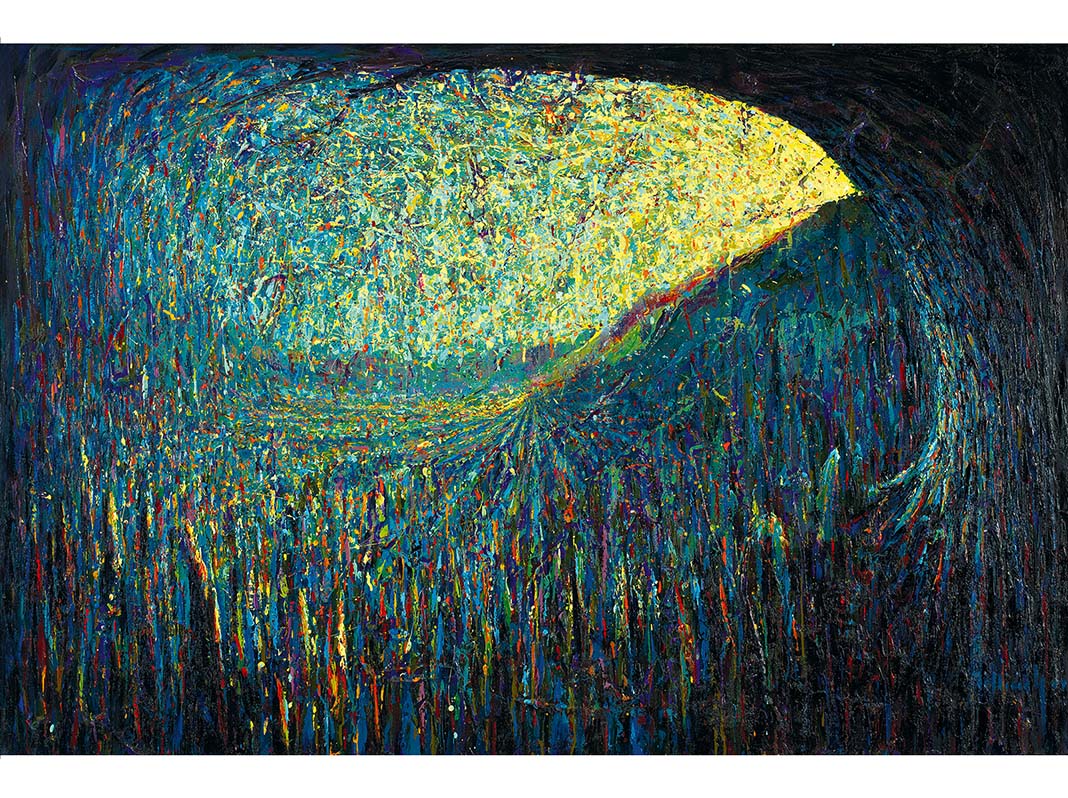

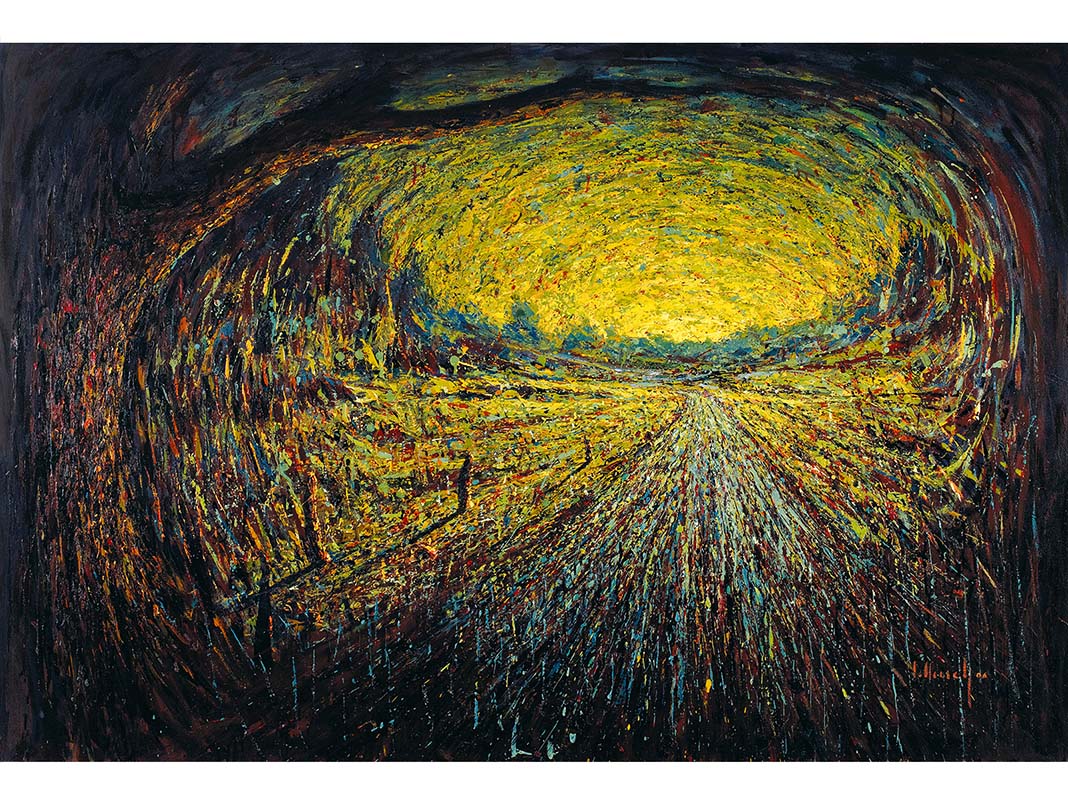

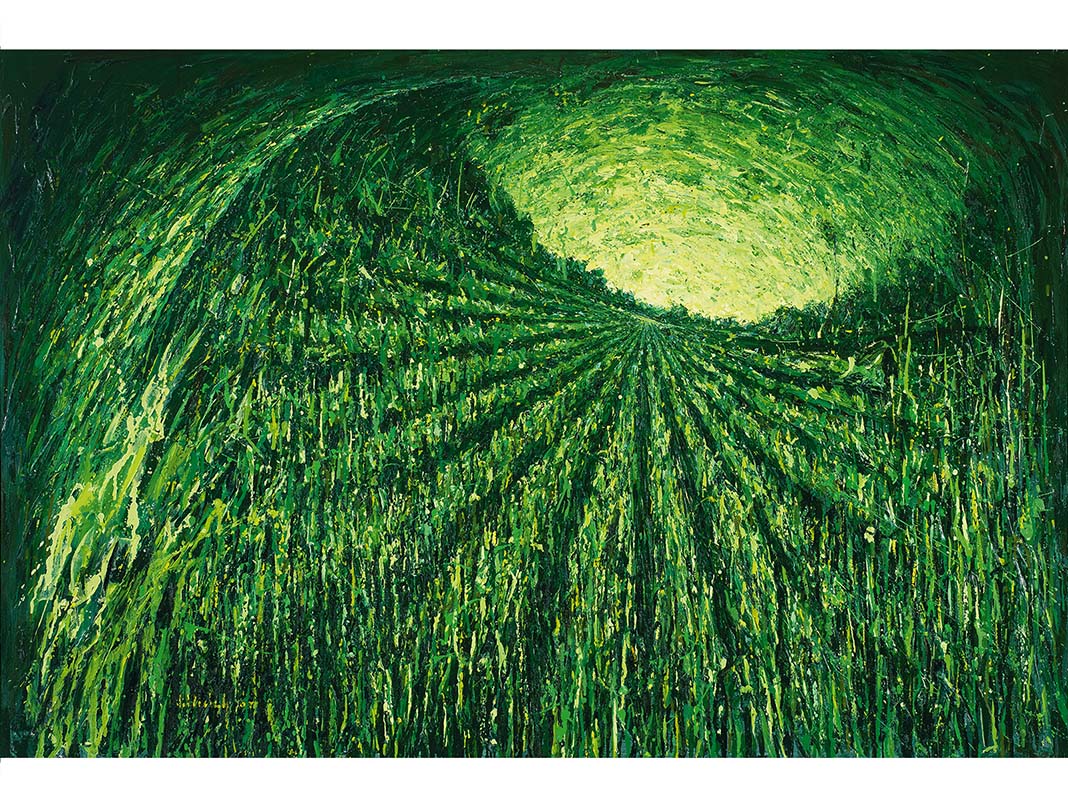

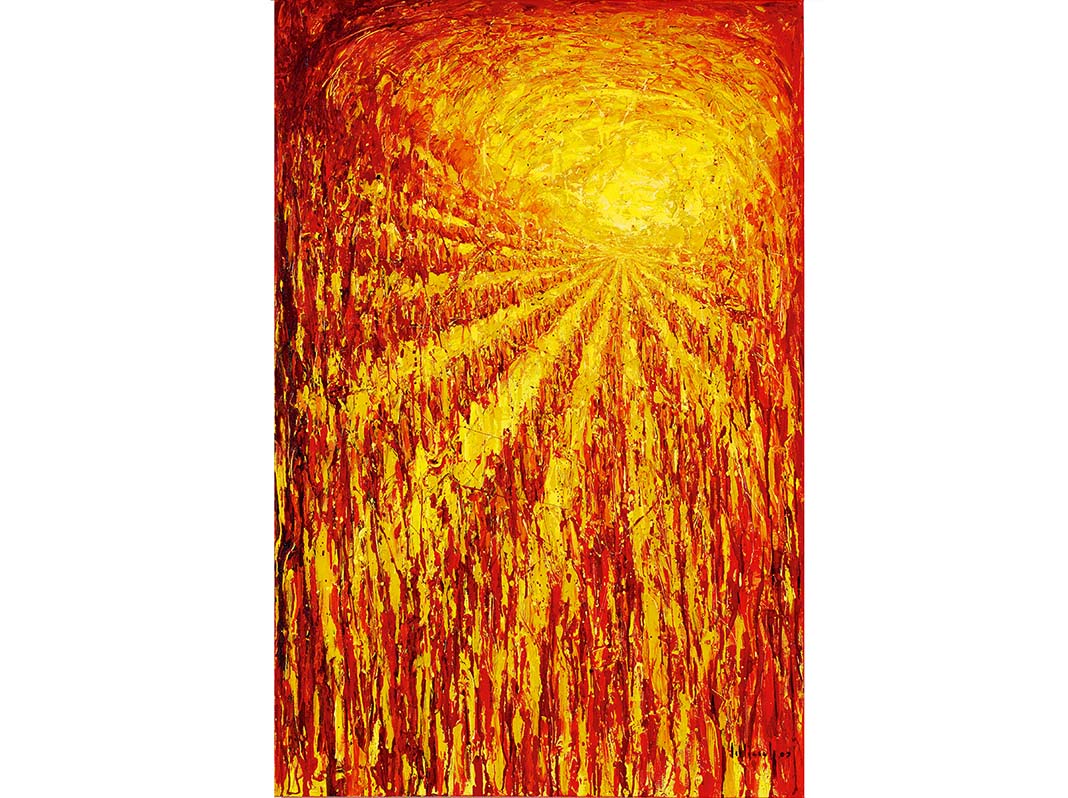

On to this energised surface, the artist applies thickly layered, tactile slashes of pure oil paint in the simplest, most spontaneous way he can in the hope of “exciting the most sensitive nerve of the viewer.” In the areas of pure light, the almost three-dimensional shapes the paint makes create a molecular dance of colour, like energized photons of light pulsating through space. The surface is alive with chaotic excitement, even when the structure of the composition attempts to pull it towards order.

Villicich talks about paintings as being like the footprints of a hunter, of someone who is searching for something that is always fleeing, like the horizon that is constantly elusive. “The horizon is only, and always, visual; you can never catch it. It is always distant. These footprints that you leave behind you are your paintings. They are the residue of the painter, the means by which you seek to express an emotion.”

In his earlier paintings, Villicich portrays human domination over nature with his inclusion of ploughed fields, fences, and built structures. The tenuousness of this imposed man-made formality becomes apparent in his later paintings. The vigour of the underpainting begins to take over. The super-structure of human imposition becomes less evident, while the chaotic energy of the oil paint plays wildly over the surface. In the large green and yellow painting, (Paesaggi #16, the last to leave the studio, fence posts are reduced to thin sticks, unconvincing as to their purpose. The ploughed fields are present, but far less visible. In the pink, red and yellow painting (Paesaggi #7), all human structures and elements have completely disappeared, except, perhaps, for the eye of the viewer which still seeks the horizon through the vortex-like centre of the composition. What is left is the essential energy of light and colour. Villicich, a collector of Australian indigenous art, is familiar with the way in which ceremonial paintings and designs drawn in the sand were destroyed at ceremony’s end. One senses something of the same happening here.

An exhibition gives viewers the opportunity of experiencing the trajectory of an artist’s thought, its translation into form. In this exhibition we see the beginning of a move away from formal compositional elements which evoke an Italian sense of landscape, to an increasingly abstract and dynamic space.

In 2006, Villicich moved to Perth with his fiancée Alessandra D’Arbe, a dancer with the West Australian Ballet. Australia’s expansive horizons and stark blue light may have played their part in loosening his connection to the more intimate nature of the Italian countryside. Or perhaps what we are witnessing is the artist disengaging from figurative boundaries to explore less constrained and freer ways of expressing the unbounded energy that is his sense of nature.

Notes

1. Curator’s translation, Pino Cacucci, Demasiado corazón, Feltrinelli, 1999 (p176)read more... read less

FRANCESCO VILLICICH

Paesaggi

PAESAGGI EXHIBITION

In memory of Simeone Villicich

(1936–2007)

CURATORS ESSAY

Jody Fitzhardinge

Curator: Fremantle, Western Australia

The mood of the paintings is at times broodingly Gothic, at times more Romantic, and here one can sense the moods of the forest at Selvino and a life lived mainly in a European environment. The application of the paint, however, takes the viewer on another journey.read more...